Place of origin:

Place of origin:

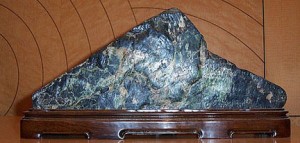

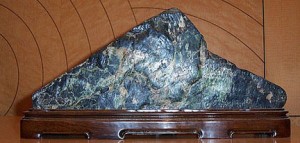

Yangkouwan of the Laoshan Mountain, Qiangdao, Shandong Province

Mineral composition:

Serpentine (metamorphic rock); pyrophyllite (a clay composed of aluminum silicate); amphibole (igneous rock)

Laoshan, in Shandong Province, is famous because the makers of Qingdao Beer use the spring water there for brewing. As early as the Song and Yuan dynasties, people collected the green stones found in the sea there as scholars’ rocks. As is recorded in the County Record of Jimo in the Qing Dynasty, Baibi, a miliary officer of Jimo, offered two Laoshan green stones to Emperor Qianlong, who was greatly delighted. Shen Xin, the Qing dynasty compiler of A Record of Grotesque Stones (Guaishi lu) wrote:

“The Laoshan stone is quite hard and the color is like that of an ancient tripod [a bronze ding, which would have had a green patina]. What is lovely is that some of the stones have white streaks, looking like melting snow. Big stones resemble erupting springs, have gullies on them and, when used as ornaments, closely matched Ying stones and Lingbi stones in elegance; small stones, on the other hand, are like yanshan [ink mountain stones].”

Laoshan stones are mainly green, and appear elegant and reserved. Normally, those of deep green color are nicknamed “sea bottom jade” (haidi yu) and those fibrous or crystal stones in light green “sea bottom jadeite” (haidi cui). The latter color usually sets off the former, forming pictures of various kinds, seen as towering peaks, rolling waves, deep green forests, fleeting clouds, lingering fog, or even urban skyscrapers. Since Laoshan stones are hard and produced in Shandong, a province with a stone collecting tradition, people today can still find some Laoshan stones collected many years ago.

Laoshan green stones vary with the depth of the water they are taken from. Those from shallow water are more fibrous in form due to their feathery crystal formation, while those from deep water are hard as jade, more compact and bulky due to the greater water pressure. It is marvelous to see jade green color on the surface of a deep green stone.

Place of origin:

Place of origin: Place of origin:

Place of origin:  Place of origin:

Place of origin:  Place of origin:

Place of origin: Place of origin:

Place of origin: Place of origin:

Place of origin: