The French scholar Rolf Stein stated that early Chinese believed that somewhere in the highest mountains there was a cave that was an exact representation of the world outside. In its center was a stalactite that gave off the milk of contentment. Any rock that suggests a mountain, cave or stalactite became symbolically important. This idea is reinforced by the Chinese notion that in addition to north and south, east and west, the most important orientation was ‘in’. it is because of this inward focus that Chinese culture looked for paradise inside of things, just as western culture looked upward and outside. in Chinese art, this orientation caused a search for ‘a world within a world’, for imagery in surprising and unpredictable places.

The French scholar Rolf Stein stated that early Chinese believed that somewhere in the highest mountains there was a cave that was an exact representation of the world outside. In its center was a stalactite that gave off the milk of contentment. Any rock that suggests a mountain, cave or stalactite became symbolically important. This idea is reinforced by the Chinese notion that in addition to north and south, east and west, the most important orientation was ‘in’. it is because of this inward focus that Chinese culture looked for paradise inside of things, just as western culture looked upward and outside. in Chinese art, this orientation caused a search for ‘a world within a world’, for imagery in surprising and unpredictable places.

Let’s imagine that early Chinese lived in limestone caves. We know that karst limestone caves are common in China, and that among their characteristics are endlessly winding tunnels. They have underground streams and lakes, skylights, even fish. The geography of this world was so complex, that people would not be able to explore and map them in a dozen lifetimes. Paradoxically, when they emerged from these caves, they could readily see and walk around the small mountains that contained these ‘worlds within worlds’.

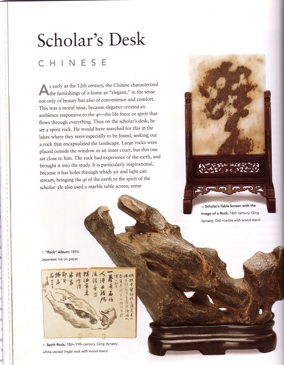

‘Scholar’s rock’ is the name commonly given to gongshi in the West. I much prefer the use of ‘spirit stone’ as it is more in keeping with the fundamental Chinese appreciation of their spiritual aspects. The term ‘spirit stone’ also evokes the deeper Daoist symbolism that was the basis for the original interest among Tang, Song, and Ming literati in these objects. Whereas ‘scholar’s rock’ reflects basic tenets of Western connoisseurship which is essentially analytical and investigative. Hence the vital role of provenance and the focus placed on appreciation of man-made objects.

‘Scholar’s rock’ is the name commonly given to gongshi in the West. I much prefer the use of ‘spirit stone’ as it is more in keeping with the fundamental Chinese appreciation of their spiritual aspects. The term ‘spirit stone’ also evokes the deeper Daoist symbolism that was the basis for the original interest among Tang, Song, and Ming literati in these objects. Whereas ‘scholar’s rock’ reflects basic tenets of Western connoisseurship which is essentially analytical and investigative. Hence the vital role of provenance and the focus placed on appreciation of man-made objects. I began collecting rocks in my twenties, more than sixty years ago. Ever since, my interest has never diminished. Western painters use human bodies as models while we landscape painters prefer rocks. Human beings, despite differences in appearance, height, proportion and weight, are on the whole not much different from one another. Rocks come from nature, and they are God’s masterpieces, widely different in shape, material, color, texture, and, more importantly, in artistic conception and charm. To depict a rock in a landscape is to paint its bones and frame. A good landscape painter has a profound understanding of the shape and surface texture of a rock.

I began collecting rocks in my twenties, more than sixty years ago. Ever since, my interest has never diminished. Western painters use human bodies as models while we landscape painters prefer rocks. Human beings, despite differences in appearance, height, proportion and weight, are on the whole not much different from one another. Rocks come from nature, and they are God’s masterpieces, widely different in shape, material, color, texture, and, more importantly, in artistic conception and charm. To depict a rock in a landscape is to paint its bones and frame. A good landscape painter has a profound understanding of the shape and surface texture of a rock. It is a time honored practice to display rocks in outdoor gardens or indoors on pedestals for appreciation. The great calligrapher and painter Mi Fu loved rocks to distraction. Bowing to them nearly everywhere he encountered them, he became known as ‘Mi the Eccentric’. The famous poet Su Shi had a passion for rocks as well and composed many beautiful verses about them:

It is a time honored practice to display rocks in outdoor gardens or indoors on pedestals for appreciation. The great calligrapher and painter Mi Fu loved rocks to distraction. Bowing to them nearly everywhere he encountered them, he became known as ‘Mi the Eccentric’. The famous poet Su Shi had a passion for rocks as well and composed many beautiful verses about them: