Category: Learn about Scholars’ Rocks

Book: Spirit Stones – The Ancient Art of the Scholar’s Rocks

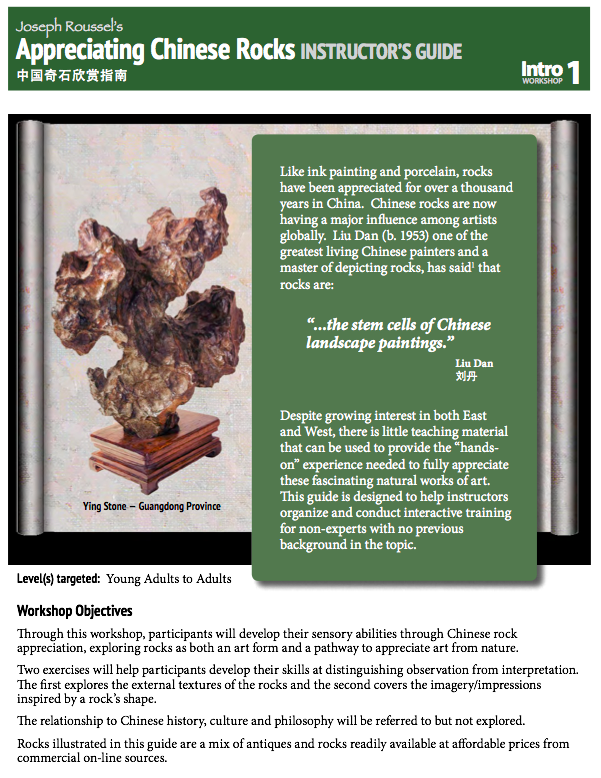

Spirit Stones – The Ancient Art of the Scholar’s Rocks

Text by Kemin Hu and Thomas S. Elias

Photography by Jonathan Singer

Brilliant photographs of scholars’ rocks, or Chinese ornamental stones, from a leading collection. Shaped by nature and selected by man, scholars’ rocks, or gongshi, have been prized by Chinese intellectuals since the Tang dynasty, and are now sought after by Western collectors as well. They are a natural subject for the photographer Jonathan Singer, most recently acclaimed for his images of those other remarkable hybrids of art and nature, Japanese bonsai.

Brilliant photographs of scholars’ rocks, or Chinese ornamental stones, from a leading collection. Shaped by nature and selected by man, scholars’ rocks, or gongshi, have been prized by Chinese intellectuals since the Tang dynasty, and are now sought after by Western collectors as well. They are a natural subject for the photographer Jonathan Singer, most recently acclaimed for his images of those other remarkable hybrids of art and nature, Japanese bonsai.

Here Singer turns his lens on some 150 fine gongshi, ancient and modern, from the world-class collection of Kemin Hu, a recognized authority on this art form. In his photographs, Singer captures the spiritual qualities of these stones as never thought possible in two dimensions; he shows us that scholars’ rocks truly are, in Hu’s words, “condensations of the vital essence and energy of heaven and earth.”

Hu contributes an introductory essay on the history and aesthetics of scholars’ rocks, explaining the traditional terms of stone appreciation, such as shou (thin), zhou (wrinkled), lou(channels), and tou (holes). She also provides a narrative caption for each stone, describing its history and characteristics.

Abbeville Press, 2014

15.7 x 12.6 x 1.6 inches Paperback, 216 pages

Other Books on Scholars’ Rocks by Kemin Hu

- Spirit Stones – The Ancient Art of the Scholar’s Rocks (2014)

- The Romance of Scholar’s Stones: Adventures in Appreciation (2011)

- Modern Chinese Scholars’ Rocks – A Guide for Collectors (2006)

- The Suyuan Stone Catalogue: Scholars’ Rocks in Ancient China (2002)

- The Spirit of Gongshi: Chinese Scholar’s Rocks (1998)

The Romance of Scholar’s Stones: Adventures in Appreciation

The Romance of Scholar’s Stones: Adventures in Appreciation

by Kemin Hu

Although Chinese scholars’ stones fascinate, they do not speak; they reveal their mysteries only grudgingly to those who take the time to observe and to investigate. In seven essays the author relates important lessons learned over a lifetime of collecting and researching these intriguing creations of nature. What did Chinese connoisseurs of a thousand years ago mean by the enigmatic terms shou, zhou, lou, and tou? Were “ink mountain stones” the earliest collected stone form, and were they valued primarily for their utilitarian function? What are the “Qingzhou stones” mentioned in one early text, but ignored in subsequent writings? What should we be looking for when we evaluate an ancient stone? How can we tell if it is ancient without written records and how much weight can be given any documentation? Finally, using the tools of connoisseurship and textual evidence, is it possible to verify that a stone first collected in the former Han dynasty is the stone we are looking at today?

Although Chinese scholars’ stones fascinate, they do not speak; they reveal their mysteries only grudgingly to those who take the time to observe and to investigate. In seven essays the author relates important lessons learned over a lifetime of collecting and researching these intriguing creations of nature. What did Chinese connoisseurs of a thousand years ago mean by the enigmatic terms shou, zhou, lou, and tou? Were “ink mountain stones” the earliest collected stone form, and were they valued primarily for their utilitarian function? What are the “Qingzhou stones” mentioned in one early text, but ignored in subsequent writings? What should we be looking for when we evaluate an ancient stone? How can we tell if it is ancient without written records and how much weight can be given any documentation? Finally, using the tools of connoisseurship and textual evidence, is it possible to verify that a stone first collected in the former Han dynasty is the stone we are looking at today?

In exploring these and other issues, Kemin Hu illuminates a depth and complexity of stone appreciation not touched upon in other publications, yet understood and appreciated by serious modern collectors as well as Chinese stone lovers of old.

$50 – buy from Amazon

2011-2012

11.2 x 8.9 x 0.7 inches Hardcover, 160 pages

Other Books on Scholars’ Rocks by Kemin Hu

- Spirit Stones – The Ancient Art of the Scholar’s Rocks (2014)

- The Romance of Scholar’s Stones: Adventures in Appreciation (2011)

- Modern Chinese Scholars’ Rocks – A Guide for Collectors (2006)

- The Suyuan Stone Catalogue: Scholars’ Rocks in Ancient China (2002)

- The Spirit of Gongshi: Chinese Scholar’s Rocks (1998)

The Symbolism of Chinese Rocks – Essay by Richard Rosenblum

The French scholar Rolf Stein stated that early Chinese believed that somewhere in the highest mountains there was a cave that was an exact representation of the world outside. In its center was a stalactite that gave off the milk of contentment. Any rock that suggests a mountain, cave or stalactite became symbolically important. This idea is reinforced by the Chinese notion that in addition to north and south, east and west, the most important orientation was ‘in’. it is because of this inward focus that Chinese culture looked for paradise inside of things, just as western culture looked upward and outside. in Chinese art, this orientation caused a search for ‘a world within a world’, for imagery in surprising and unpredictable places.

The French scholar Rolf Stein stated that early Chinese believed that somewhere in the highest mountains there was a cave that was an exact representation of the world outside. In its center was a stalactite that gave off the milk of contentment. Any rock that suggests a mountain, cave or stalactite became symbolically important. This idea is reinforced by the Chinese notion that in addition to north and south, east and west, the most important orientation was ‘in’. it is because of this inward focus that Chinese culture looked for paradise inside of things, just as western culture looked upward and outside. in Chinese art, this orientation caused a search for ‘a world within a world’, for imagery in surprising and unpredictable places.

Let’s imagine that early Chinese lived in limestone caves. We know that karst limestone caves are common in China, and that among their characteristics are endlessly winding tunnels. They have underground streams and lakes, skylights, even fish. The geography of this world was so complex, that people would not be able to explore and map them in a dozen lifetimes. Paradoxically, when they emerged from these caves, they could readily see and walk around the small mountains that contained these ‘worlds within worlds’.

Spirit Stones – Essay by Ian Wilson

‘Scholar’s rock’ is the name commonly given to gongshi in the West. I much prefer the use of ‘spirit stone’ as it is more in keeping with the fundamental Chinese appreciation of their spiritual aspects. The term ‘spirit stone’ also evokes the deeper Daoist symbolism that was the basis for the original interest among Tang, Song, and Ming literati in these objects. Whereas ‘scholar’s rock’ reflects basic tenets of Western connoisseurship which is essentially analytical and investigative. Hence the vital role of provenance and the focus placed on appreciation of man-made objects.

‘Scholar’s rock’ is the name commonly given to gongshi in the West. I much prefer the use of ‘spirit stone’ as it is more in keeping with the fundamental Chinese appreciation of their spiritual aspects. The term ‘spirit stone’ also evokes the deeper Daoist symbolism that was the basis for the original interest among Tang, Song, and Ming literati in these objects. Whereas ‘scholar’s rock’ reflects basic tenets of Western connoisseurship which is essentially analytical and investigative. Hence the vital role of provenance and the focus placed on appreciation of man-made objects.

Western study is objective and scientific and generally lacks or downplays the spiritual challenge of Chinese art. Thus it is difficult to appreciate objects in their natural form. New York’s Museum of Modern Art has no natural objects in their collection, and apart from a few spirit stones, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has only man-made objects. Consequently, there is a tendency to regard rocks as geological rather than spiritual objects and to appreciate them by rock type rather than for their aesthetic appeal.

Rare Rocks are God’s Creations – Essay by C. C. Wang

I began collecting rocks in my twenties, more than sixty years ago. Ever since, my interest has never diminished. Western painters use human bodies as models while we landscape painters prefer rocks. Human beings, despite differences in appearance, height, proportion and weight, are on the whole not much different from one another. Rocks come from nature, and they are God’s masterpieces, widely different in shape, material, color, texture, and, more importantly, in artistic conception and charm. To depict a rock in a landscape is to paint its bones and frame. A good landscape painter has a profound understanding of the shape and surface texture of a rock.

I began collecting rocks in my twenties, more than sixty years ago. Ever since, my interest has never diminished. Western painters use human bodies as models while we landscape painters prefer rocks. Human beings, despite differences in appearance, height, proportion and weight, are on the whole not much different from one another. Rocks come from nature, and they are God’s masterpieces, widely different in shape, material, color, texture, and, more importantly, in artistic conception and charm. To depict a rock in a landscape is to paint its bones and frame. A good landscape painter has a profound understanding of the shape and surface texture of a rock.

Chinese painting, both in past and present, focuses on texture and brushwork. Truthful depiction of landscape was valued in ancient Chinese painting from the Five dynasties (907-960) until the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) when Ni Zan shifted the focus to use of the brush.