Shou Zhou Lou Tou (SZLT)

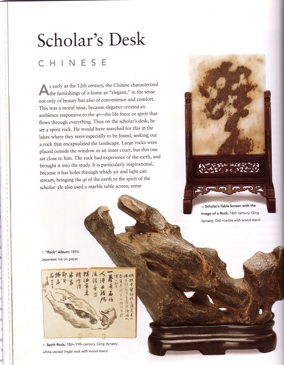

The great Song literati Mi Fu formed an appreciation of rocks based on his own aesthetics as well as what he knew of past collections. The four categories he considered essential to the appreciation of rocks were shou, zhou, lou, and tou. These four criteria are still used by connoisseurs today, especially for Taihu rocks.

Shou means thin and with respect to rocks, it means an elegant, slender shape, ‘vertically oriented, erect and alone’. (see Figure 1)

Zhou means wrinkles and refers to rich surface textures and furrows created from delicate intaglio lines and relief ridges that show rhythms and changes in shape. Thus a small rock can embody the topographic features of hills and mountains. (see Figure 2) In Hangzhou, the rock known as ‘Wrinkling Cloud Peak’ combines both shou and zhou. (see Figure B)

Lou means channels and other types of indentations that lend an exquisite beauty to rocks. These channels are linked to one another as if a path were unfolding itself through the rock. (see Figure 3)

Tou means holes and openness. Air and moonlight can pass through such openings. (see Figure 4) In Shanghai, the rock known as ‘Exquisite Jade’ combines both lou and tou. (see Figure A)

Figure A – ‘Equisite Jade’ Figure B – ‘Wrinkling Cloud Peak’

Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4

It is a time honored practice to display rocks in outdoor gardens or indoors on pedestals for appreciation. The great calligrapher and painter Mi Fu loved rocks to distraction. Bowing to them nearly everywhere he encountered them, he became known as ‘Mi the Eccentric’. The famous poet Su Shi had a passion for rocks as well and composed many beautiful verses about them:

It is a time honored practice to display rocks in outdoor gardens or indoors on pedestals for appreciation. The great calligrapher and painter Mi Fu loved rocks to distraction. Bowing to them nearly everywhere he encountered them, he became known as ‘Mi the Eccentric’. The famous poet Su Shi had a passion for rocks as well and composed many beautiful verses about them:

Place of origin:

Place of origin: